Damage Control

Hundreds of thousands of goods in transit are damaged each year. Determining who picks up the bill is a multibillion dollar question

During February 2014, Danish container ship Svendborg Maersk sailed from Rotterdam in the Netherlands, bound for Sri Lanka. The next day, off the coast of France, the ship was unexpectedly

struck by strong winds and high waves, and by the time she limped into the Spanish port of Malaga, 520 containers had been lost overboard. Another 250 units had been damaged.

Fortunately, 442 of the containers were subsequently declared to be empty, but the accident remains one of the worst losses of cargo in peace time history. It was also a drop in the ocean compared with the total volume and cost of freight damaged in transit each year, and the astronomical bill that comes with it.

According to the International Transport Forum (ITF), an intergovernmental think tank with 60 member countries, 108 trillion tonne-kilometers (a tonne-kilometer or tkm is a unit of measurement representing one tonne of goods transported over a distance of one kilometer) of freight was transported around the world in 2015. Seventy percent of that freight traveled by sea and 18 percent by road, with the rest moving by rail, inland waterway and air. How much of this cargo arrived ‘out of spec’—a term widely used in industry to indicate received goods that were not delivered in acceptable condition—is anyone’s guess.

The Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA) and the Food Marketing Institute (FMI) estimate about half a percent of consumer products are subject to shipping damage each year, which amounts to about $1 billion of losses. But that is just consumer goods in the U.S., the real number will be a magnitude higher.

Take for example the world’s largest online retailer Amazon; the company controls almost half of U.S. online sales and spent nearly $38 billion on shipping costs in 2019. However, according to Forrester Research, approximately 25 percent of all items bought online are returned, with the Narvar Consumer Report 2019 claiming that 21 percent of Amazon’s returns are due to the item arriving damaged. Eliminating damage in transit would save companies a lot of money.

Why things arrive damaged

Whether it is a shipment of luxury cars, a television set, or a vanload of perishable goods, according to British packaging company, GWP Group, the reason why things arrive damaged almost always falls into one of eight categories; impact, vibration, moisture, dust, temperature/ humidity, poor handling, electrostatic discharge (ESD), or incorrect packaging.

GWP Group says impact is the most common way that equipment or products become damaged in transit, usually as a result of products being dropped, collisions while on the move or even individual items crashing into each other inside their packaging. Vibration is also a major source of damage particularly if that vibration matches the resonant frequency of the product.

Dust is a risk factor in particular for electronic equipment. It not only inhibits the movement of air, but also attracts moisture, which increases the risk of corrosion, short circuits and spoilage. Moisture can also be introduced via leaks, spillages and rain with similarly harmful results, while temperature extremes can not only spoil perishable goods, but cause components to deform if the heat becomes too high, or brittle and degrade if too low.

Lastly ESD can play havoc with electronic products, and packaging specifically designed to combat ESD is critical to their safe transportation and storage and to mitigate the risk of catastrophic failure. Static electricity can be caused by a range of factors, not least other devices, friction and climate.

“If you are sending out extremely high value, or fragile products that cost thousands ... then corrugated cardboard packaging is unlikely to be the best solution,” says Richard Coombes, General Manager with GWP Protective. “It is worth thinking about the cost of packaging versus the cost of having to replace returned items or faulty equipment.

“If a protective case with custom foam costs £300 [$370] to provide the optimum level of protection, but the cost of replacing a specialist part would cost £5,000 [$6,100] or more, then it does not make sense to underspecify the packaging.”

Counting the real cost

Even with careful handling and appropriate packaging, accidents happen, and when goods arrive at their destination spoiled, damaged or broken, someone has to pay, and the cost goes well beyond the invoice cost or the item’s retail value. The true cost of in transit damage has to factor in a myriad of other outlays; repackaging, return freight, replacement, administrative costs, reshipping and compensation, just for starters. Then there are the intangibles, damage to a company’s image, brand equity, potential loss of customers and so on.

Who picks up the bill can be a contentious and complex issue, and one that needs to be addressed in the contract of carriage by the owner of the goods—both seller and buyer—as well as the carrier and its insurers. According to J. Paul Dittmann, Executive Director of the Global Supply Chain Institute at the University of Tennessee, it would be wrong to assume a carrier will be wholly responsible for any damage while they are in possession of your cargo. Standard carrier liability is not insurance, and in fact he says, is there to protect the carrier not its customer.

For the most part, carrier liability covers up to a certain dollar amount per pound of freight, protecting the carrier from uncapped losses, as well as damage caused due to ‘Acts of God’ or shipper negligence (improper packaging or loading, for example). The onus can then be on the shipper to prove the carrier is at fault, which hasn’t traditionally been easy to establish. Most contested cases typically become disputes between the carrier’s insurers and the insurers of the goods in transit, and when that dispute cannot be resolved, in turn by their respective legal representation. But now technology is available that can help establish what went wrong and when, and settle cases before they end up as disputes between expensive legal teams.

How tech can help

Using technology to track freight through the supply chain is already well established. The Bill of Lading (in effect the receipt for the cargo being shipped by the carrier) will in addition to a range of details about the freight contain a progressive, or PRO, number. This PRO number is used to create a barcode that’s printed on a sticker and placed on the parcel or pallet, so it’s visible and scannable. When scanned during freight handling, this is the simplest way to establish the last known whereabouts of freight - but offers little other information.

RFID-based tags are also commonplace and eliminate the manual process of scanning a barcode. Passive RFID tags are cost effective but with limited data storage don’t offer much more insight into cargo than a barcode, require additional infrastructure and cannot actively track the movement of freight through the supply chain in ‘real time’. Active, battery powered RFID tags can function as a beacon to provide live data on the location of cargo and can support sensors that measure and transmit environmental data such as temperature, humidity and light. They also offer larger memory for data storage, but to provide this data in real time still requires receiving infrastructure and a gateway at every step of the journey to relay the information to the Cloud. Then there is the not inconsequential issue of cost. A passive RFID tag typically costs between 10 and 50 cents, an active tag can range anywhere from $5 to 15, making it impractical as a solution for individual item tracking unless the value of that item can justify it.

Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) receivers are useful not only for tracking a ship, truck or delivery van’s whereabouts, but can also be paired with sensors and a long range radio transceiver or cellular modem to enable live tracking of high value freight via the Cloud. Cost is again an issue, making the use of such systems for singular pallets let alone individual items unrealistic for all but essential applications.

The large scale rollout of the new IoT targeted LPWAN version of cellular wireless technology—called LTE-M and NB-IoT—in the last 12 months, may well offer a better alternative. Cellular IoT devices such as Nordic Semiconductor’s nRF9160 low power SiP with integrated LTE-M/NB-IoT modem and GPS offer the ability to track and monitor the condition of assets across cities, countries, or even the globe without recourse to a gateway or any additional infrastructure. Cellular is also as reliable and secure as wireless tech gets and, depending on the application, multiyear battery life can be expected.

While not yet economical enough to be employed at the individual parcel level, these devices can be easily incorporated into modules teamed with Bluetooth LE transceivers and then paired with relatively inexpensive Bluetooth LE-powered sensors. With the long- and short- range wireless protocols working together seamlessly, real time end-to-end supply chain monitoring of an individual parcel’s whereabouts and, for example, movement, impact, orientation and environmental data is possible.

Nordic recently demonstrated a concept based exactly on this premise, nRF Pizza. Individual pizza boxes fitted with the Nordic Thingy:91 cellular IoT development tool (which incorporates an nRF52840 advanced Bluetooth SoC and a Bosch BME680 environmental sensor) recorded location, temperature, pressure and acceleration data, enabling a customer via an app to not only follow their pizza’s location as it travels from the store to their home, but also see if it has gone cold, or has been dropped or flipped. While the concept is light-hearted, this technology applied to determining liability in the billions of dollars of claims each year arising from goods damaged in transit is now gaining serious traction.

“Environmental asset tracking is emerging as a prime early use case in industrial IoT,” says Geir Langeland, Nordic Semiconductor’s Director of Sales & Marketing. “This is being driven by a compelling and clear cut benefits analysis centered around the cost savings that can be made from avoiding lost, wrong or spoilt consignments, and at the same time reducing the risk of disappointing or even losing valuable end customers.”

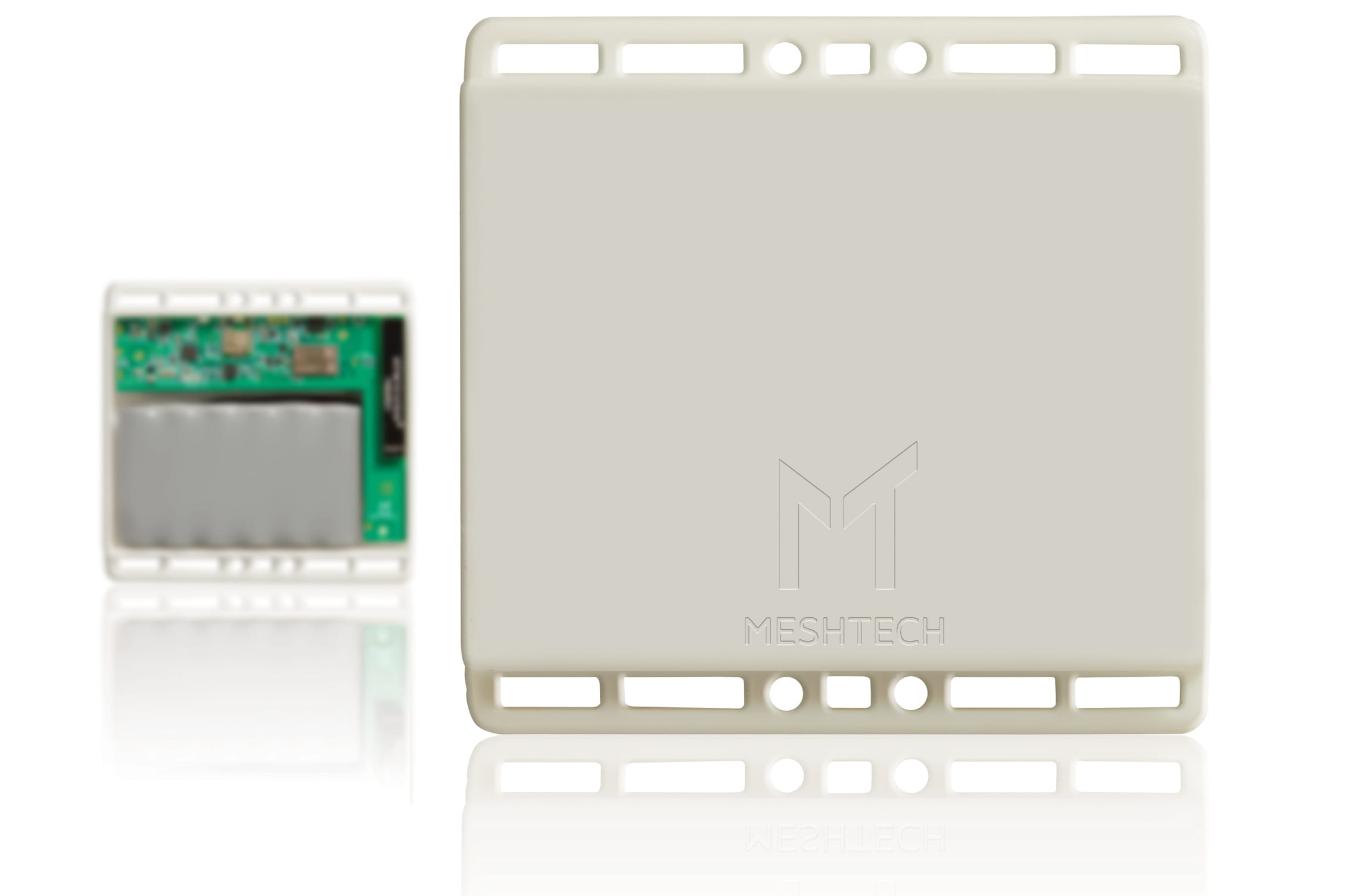

One company pioneering this technology is Norwegian asset tracking and monitoring specialist Meshtech. Last year the company announced development of an environmental asset tracker combining cellular IoT and Bluetooth LE technologies, designed to provide perishable goods suppliers and logistics companies with end-to-end ‘live’ visibility of perishable goods in transit. The Meshtech Cloud Tracker can not only continuously monitor environmental parameters such as temperature, but also whether a consignment has been dropped, tilted or folded, the location of individual shipping items within a consignment, the order in which they were loaded and unloaded, and the geographical location of the entire consignment anywhere in the world.

The Meshtech CloudTracker provides perishable goods suppliers and logistics companies with end-to-end ‘live’ visibility of perishable goods in transit

Employing both Nordic Semiconductor’s nRF9160 SiP and nRF52811 Bluetooth LE SoC, the device relays sensor data to the Cloud every thirty minutes, for example alerting vested parties if a consignment of perishable goods exceeds its specified temperature range or is dropped or otherwise mishandled. This potentially allows the carrier to take immediate corrective action to save the goods, as well as providing traceability and evidence in the event of an insurance or compensation claim.

“Cloud Tracker is designed to detect delivery or storage issues quickly enough that they can be corrected without jeopardizing an entire consignment,” says Meshtech Interim CEO, Preben Skretteberg. “Perishable goods suppliers now have a viable way to prevent unnecessary compensation costs, while also being able to exceed both current and [increasingly strict] future regulations that may apply to the shipment and storage of perishable goods. The next step is to take the Cloud Tracker beyond perishable goods, and we are already in discussions with multiple large enterprises in other market segments and industries regarding this.”

As the technology and infrastructure matures, the cost of cellular based tracking systems will fall, to the point tracking and condition monitoring systems for low unit cost goods such as pizzas could become a commercial reality. Then the goal will be to not only locate, but also know the condition

of any individual item of freight, at any time, anywhere on our planet. Even inside a shipping container in the middle of the ocean, potentially 1600 km from the nearest cell phone tower and where the closest human life bar the ship’s crew can be found on the International Space Station.

The technology already exists, as the data can in theory be relayed via the ship’s own communications system and satellite, but it remains way off a cost-effective prospect. Not that it would have saved the Svendborg Maersk from her unfortunate fate, but it could help settle the multibillion dollar blame game that is goods damaged in transit.